Cattle Origins & Cultures of the Continental United States

Prior to the publication of Terry G. Jordan’s North American Cattle-Ranching Frontiers: Origins, Diffusion, and Differentiation (1993), Christopher Columbus was often credited with the spread of cattle from Spain to the New World. However, you won’t find Columbus’s name in Jordan’s massive scholarly study which is the most recent volume in the Histories of the American Frontier Series.

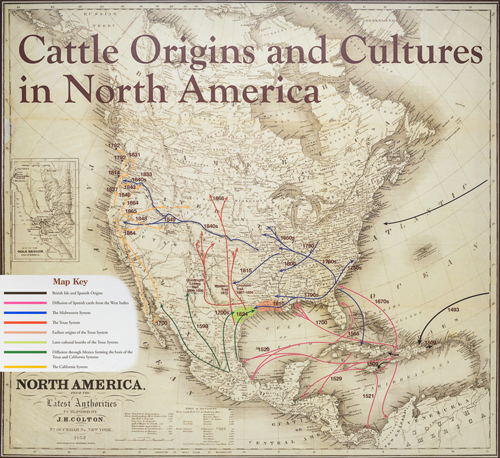

Terry Jordan, who passed away in 2003, was a cultural geographer with a reputation of meticulous scholarship who based his monograph on diverse primary and secondary sources as well as qualitative geographical research techniques. He is not interested nor gives credit to the transport company who first brought cattle to the West Indies from Spain but rather his focus is on the roots of the distinct cattle cultures of the Americas and how these cultures spread from their beginnings in British colonies or the West Indies into North America. It is important to note we are studying two things: cattle cultures which deal with the human skills and techniques developed to handle cattle and cattle cradle hearths or the introduction and dispersal of cattle. This exhibit is based on Dr. Jordan’s scholarly work.

Cradle Hearths of North America

Spain

Through extensive research, Jordan discusses the cattle ranching areas of Spain particularly the provinces of Extremadura and Andalucia which contributed heavily to the colonization of cattle and people to the West Indies in the late Fifteenth century. From the Greater (Cuba, Hispaniola – Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Puerto Rico) and Lesser Antilles (double arc of islands from the Virgin Islands to Trinidad) where transplanted Spanish cattle thrived in the lush tropical climate, the bovine were dispersed to Florida, Central Mexico and areas along the Gulf coast of North America. From these points they migrated northward into what is today Texas and Louisiana.

California System

These Spanish cattle were also taken north from Sonora, Mexico into California with the Spanish as they explored their conquests and established the mission system. Some cattle were trailed or shipped as far north as the Willamette Valley and Puget Sound and eventually mixed with “higher grades” of cattle that were introduced by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Oregon emigrant’s Middle West derived stock. Terry Jordan mentions the transplanting of cattle to Spanish outpost settlements in the 1790s at Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula and Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. Jordan’s research reveals that as early as 1837 Iberian longhorns were trailed overland from California to the Willamette Valley to supply the newly arrived emigrants with fresh stock.

Not only did California cattle travel northward into Oregon and Washington country but many trekked trans-Cascadia and supplied the Mormon settlements in the Great Basin in 1848 (Jordan, p. 245) and later helped to stock the ranges in Nevada, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming between 1878 and 1883.

Midwestern System

Known as the Midwestern System this cradle hearth draws its genetics from the British Isles. Cattle were part of the English colonies to the Atlantic coast in the early 1600s where they along with their masters struggled to gain a foothold in the New World. Eventually from this precipice along the Atlantic coast, the cattle and the colonists began to spread westward along a “coastal plain corridor of pine barrens, a path that led them eventually beyond the Mississippi River to the great western prairies”. It is here that they come into contact and mix with cattle of Spanish influence.

These cattle of Durham heritage, the basis of the Midwestern System are the “black cattle” (early Celtic terminology to distinguish a bovine from an ovine) that overland emigrants used to pull their belongings as they pushed the frontier west. Some of these oxen were destined to become ‘pilgrim cattle’ or cattle that wore out along the trail and were abandoned. Some survived and fattened and were captured and resold or slaughtered. Those that made it to Oregon country became the basis for herds of cattle that generations later were trailed back to the ranges east of the Cascades.

Texas System

The Texas system which ascended into the Great Plains from 1866-1885, is viewed as one of the most rapid advancements of Euromerican movement into the American west. Maybe it is because of this phenomenon or because of the volumes of material written about the trail drives from Texas, but most Americans identify the Texas system as the only cattle hearth and culture in the United States. Because the Texas system will be discussed in more detail at a later time during research of the trails from Texas, the focus will turn to the cattle cultures of each system.

Cattle Cultures

The three historic cattle cultures or systems of cattle ranching in the United States are:

- The Texas System (Spanish/British Hybrid)

- The California System (derivative of central and western Mexico and eventual British mixing)

- Midwestern System (derivative of British cattle by way of upland south and Ohio River Valley)

Terry Jordan’s work concentrates on the culture of each of these cattle ranching systems. He believed that there was a clash between these systems on the Great Plains of the United States and Canada and the eventual winner was the Midwestern System. His main premise is that cattle ranching in what is now the United States is not a representation of New World adaptations to physical geography but instead a dispersal of herding cultures that are firmly rooted in Southwestern Iberia, the sub-Saharan steppes of West Africa and the British Isles.

This view clashes with ideas first proposed by Walter Prescott Webb the renowned Great Plains historian who encouraged generations of historians and geographers to believe that humans were subject to forced adaptations in institution and lifestyle before settlement could occur. In 1931, Webb’s views of frontier and settlement were seen as the ‘new interpretation of the American West’. It is ironic as it is fitting that Webb’s hypothesis which has held sway all these years is being challenged by Terry G. Jordan the professor who held the prestigious Walter Prescott Webb Chair in Geography at the University of Texas, Austin.

Jordan categorizes each cattle herding system according to what we would call herdsmanship; human contact and or care of cattle. The Texas System consists of minimal human contact and care. Cattle are left to their own defenses which is what brought about the demise of the Texas System. When Texas cattlemen ventured out of their warm subtropical climate into the ranges of the northern Great Plains they failed to make the necessary adjustments to animal husbandry and disaster struck. The Texas System is a perfect example to refute Webb’s thesis. It is also important to note that Jordan believes that Louisiana not Texas, “played the crucial role in transfer of Spanish techniques to Anglo-American cattlemen”.

The California System was a blending of both the intense care of cattle found in the herders that descended from the British Isles and those cultural traits found in the Texas System. Some herders put up hay, formed cattle organizations and moved cattle from summer to winter ranges while others did not. Evidence of the latter is seen in the phenomenal death loss of cattle trans Cascadia the same winter of the ‘Great Die Up’ on the Great Plains.

Eventually the Midwestern System prevails as cattlemen realize that in order to survive and use the ranges of the Great Plains, cattle have to be fed during the winter, cattle organizations are formed to help implement laws and rules to prevent theft and promote views, fencing helps control grazing and allows for improvement in the herd through selective breeding and improves range utilization providing for winter and summer ranges as well as areas to harvest hay or other forages and grains for winter supplementations.

Explanation of the different systems and the triumph of the Midwestern System are important, but not the most prominent theme that Jordan concludes in this study. He emphasizes that it is important to dispel the myths of a single monolithic cattle ranching frontier that was entirely developed culturally as an American system due to the physical geography. His study reveals that the cattle frontier was pluralistic in nature with diverse antecedents and that the techniques of each cattle culture were not developed in the American west but carried here from earlier cattle cultures in other parts of the world.

These cultures in turn can be defined further as to originating in lowland or highland areas. Jordan found differences in herdsmanship due to the type of geography the European herder hailed from. Maybe in that small acknowledgement Jordan does give credence to his mentor Professor Webb that physical geography at one time in history did play a role in development of cattle culture in other parts of the world, but not on the Great Plains.