The Cowboy

The reign of the cowboy lasted less than a few decades but occurred at a juncture in American history to create fodder for generations of books, film and song that propelled the ordinary cow chaser of the late 1800s to mythical status. The cowboy was seen as the last frontiersman and the open range as the last American frontier. These ingredients set the stage for the making of an American folk hero who will forever epitomize individualism and freedom in the nation’s imagery.

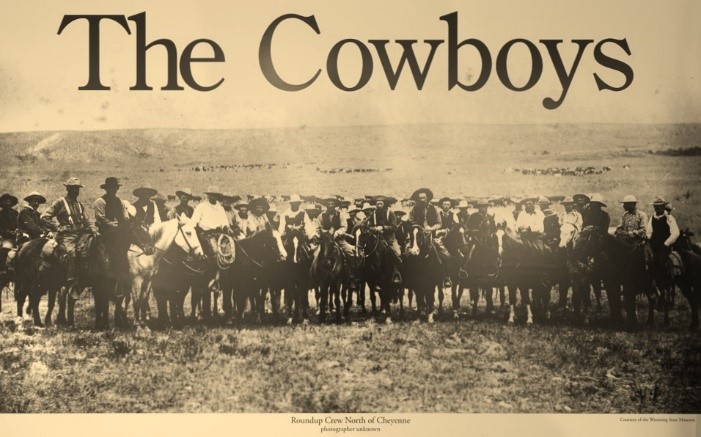

Cowboys were a diverse group of adventurous young men. Many were disillusioned Civil War veterans or sons of farmers looking for a new start. Some were freed slaves while others were the descendants of the ‘original’ cowboys, the vaqueros of Mexico.

A cowboy who ‘hired on’ to trail a herd of cattle north was paid about $1 per day for his services. Cowboys with some trail experience were generally assigned the job of ‘point men’ and it was their job to keep the cattle in the lead moving in the right direction. Some cowboys rode 'flank' or to the sides of the herd and kept the long column from spreading out over the prairie. The most inexperienced riders or ‘greenhorns’ spent the day riding drag, choking on dust and pushing the slower cattle at the very rear of the herd.

A drive averaged between 1,500 to 2,000 head of cattle with seven to 10 cowboys making up the crew. For about $125 per month pay, the trail boss oversaw every aspect of insuring that the herd and the cowboys made it to the end of the trail. It was the trail boss who hired and fired the cowboys, scouted water and grass along the way and saw to it that the tally was correct. Toward evening, cowboys on a trail drive would gather the cattle into a tighter bunch and push them off the trail to graze. As the sun set, the herd was hazed to an area the trail boss had selected to bed the herd down for the night. Cowboys who were to ‘ride night herd’ would rope their night horses from the remuda and saddle up for their turn at watching over the herd. The night herders would slowly ride around the herd in opposing circles singing soft lullabies to calm the cattle and get them to lie down.

Oh, say little doggies, when will you lie down

And give up this shifting and roving around?

My horse is leg weary, and I’m awfully tired but

if you get away, I’m sure to get fired

Lie down, little doggies, lie down

Hi-yo, hi-yo, hi-yo!

The Bunk house exhibit - click on an image, for a quick tour, then learn more below!

Learn More

- Choose question