High Plains Ecology

Grasses

Two of the native grasses that are components of the shortgrass prairie are shown in this display. On the left is Little Bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium

On the right is Western Wheatgrass, Agropyron smithii

A plant that grows in the cool season.

Fire

Fire was a driving ecological force on the prairies. Lightning caused fires that would burn the prairie every few years. With the introduction of Paleoamericans 10,000 to 13,000 years ago, the frequency of fire increased. American Indians had a dozen documented uses of fire and their frequent use of it as a land management tool is well known and had a significant impact on the ecology of the landscape. Fire, like grazing, forced the plants to keep their growing points low to avoid being burnt or grazed off, and to store reserves to initiate growth the next year. A class on Rangeland and Fire Ecology is offered at Chadron State College as part of its Agriculture and Rangeland Management degree program.

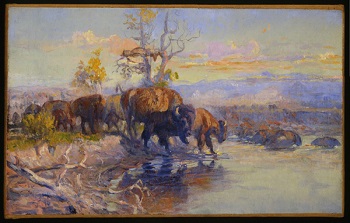

Bison

Grasslands began to develop during the Eocene, about 45 million years ago, and became well established in the Miocene, about 16-14 million years ago. During this time frame there was a maximum diversity of ungulates (hoofed animals) including many grazers. The climate was moderate and became increasingly drier with the Rocky Mountain Uplift. Fires, drought, and grazing were common evolutionary factors that influenced the grass plants to develop deep, widespread roots and some underground stems called rhizomes. This favored the grasses over trees, and thus the treeless plains of the prairies.

Early Range Cattle

The introduction of early range cattle replaced the presence of bison on the prairies and replicated the natural grazing process, as early ranchers learned that forage plants cured while standing and remained available for grazing through the fall and winter. Texans abandoned their traditional practice of burning the range in order to preserve the grasses for winter grazing. With time, cattle ranching on the open range flourished with massive ranches from central Mexico to Montana all grazing the open range.

Today

Once, the grasslands of North America formed the largest grassland complex in the world. Now these naturally sustainable grazing lands supply over one-half of the forage for rangeland livestock producing the majority of all calves born in the U.S. In Nebraska almost one-half of the state is rangeland and forms the foundation of the Nebraska ranching industry. This is all made possible by the evolutionary pressures of periodic fire and tens of thousands of years of grazing by ungulates.

Chadron State College offers a number of courses focused on the scientific management of grasslands as part of its Agriculture and Rangeland Management degree programs